Noxubee County Library

103 East King Street

Macon, Mississippi

N.B. Revised 28 December 2017.

Postcard Collection.

Sitting in a jail cell in the newly opened Noxubee County Jail in 1907, Si Connor was visited by Jesus. “Jesus have been here since I been in jail and have taken me to hell and showed me everything there, and what sort of place it is,” he told a reporter a couple weeks before his execution. Connor was shown a “big fire” with a “man toting water to the folks in the fire.”

“Hell,” continued the inmate, “is a right big place. Yassah, I spec it is as big as Macon, maybe bigger.” In preserving the African-American man’s dialect, the unnamed reporter from the Macon Beacon showed no compassion for the man’s vision, based on race and class. Interestingly, Connor points out that the fire contained both whites and blacks.

Connor’s next vision took him to the gallows that had been erected for his own state-sponsored demise. The sheriff put the noose around his neck and a pair of angels appeared and told him, “Si, don’t you be skeered or shamed or nothing for you is a child of God.” The angels flew him to heaven where he was greeted by his grandmother, sister, and “my little baby.” “I saw lots of Noxubee county folks up there. Yassah, white people too.” Continuing in his vision, Connor replies, “Jesus Christ told me to tall all the people down here to believe in him and He would save them.”

The reporter notes that “the condemned man tells all this with earnestness and sincerity, but with the same silly smile he wore when on the witness stand telling of killing his wife with an ax.” The jailer is quoted saying that Mr. Connor “has no dread of death, saying he wants to stay here as long as he can but is ready to go and doubtless he is. As a horrible example to a portion of his race, he will prove a failure.”

Allow me to round out the scene with a bit of local history. In 1830, sixty Choctaw leaders met with government agents at a place with the marvelous name of Dancing Rabbit Creek. There the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek was signed on the 27th of September ceding some 11 million acres of Choctaw land east of the Mississippi River to white settlers in exchange for some 15 million acres in Oklahoma.

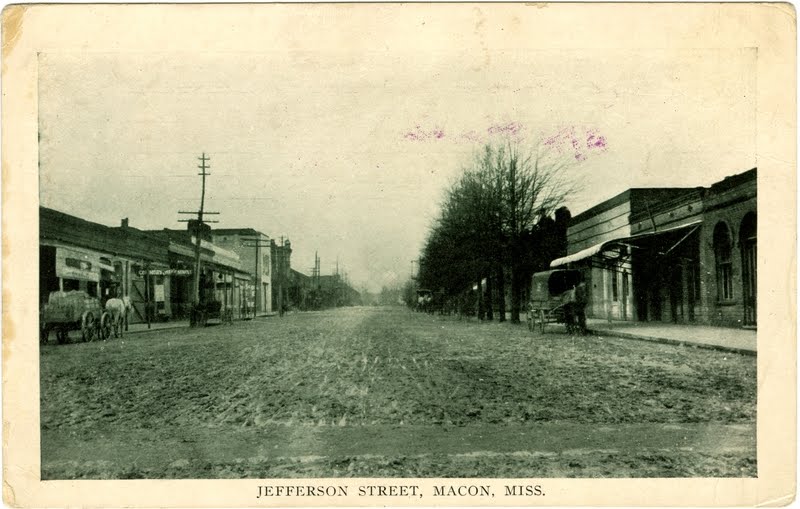

The ceded land became a huge swath of what is now the state of Mississippi and a small portion of western Alabama. In 1833, the portion of the ceded lands around Dancing Rabbit Creek was established as Noxubee County, so named for the Noxubee River; meaning “stinking water” in the Choctaw language. Near the center of the county, on the Noxubee River, the town of Macon was established as the county seat. The town prospered and, according to the 1938 WPA guide to Mississippi, “the big white- columned homes are the remaining evidence.”

As Sherman burned the state capital, Jackson, during the Civil War, the state government moved to Macon temporarily, setting up business at the Calhoun Institute, one of a handful of schools in and around Macon. Two sessions of the state legislature met in these school buildings while one of them, as well as many of Macon’s church buildings, were commandeered for hospitals.

Most histories of the area seem to stop just after the turmoil of the Civil War, so one might be tempted to assume that the town returned to being a sleepy hamlet. Judging from the population numbers in the 1938 WPA guide (2,198 people) and the numbers provided by Wikipedia (2,461 people in the 2000 census), it seems that little has changed throughout the bulk of the twentieth century.

The original Noxubee County Jail was constructed in Macon in 1860, on the eve of the Civil War. Around the time the new jail was constructed, the old jail was described by a local attorney and state representative as being, “no jail at all.” Unfortunately for the local citizenry, the old jail was regularly the scene of prisoners simply removing bricks from the masonry walls to escape.

Hailed for its luxurious appointments, the new jail offered “steam heat, electric lights, hot and cold baths and ‘saw and file-proof cells,” which “will minister to [the prisoners’] comfort and pleasure their sense of the magnificent.” The new facility was constructed by the Pauly Jail Company, a company out of St. Louis that has been constructing correctional facilities since 1856. Quite a number of the historic (and haunted) jails remaining throughout the South were constructed by this company.

Recognizing the need for a modern facility, a new jail was constructed in 1978. The historic importance of the old jail was noted and the building was added to the National Register of Historic Places the same year it closed. In 1983, the building was renovated for use as a public library all the while maintaining some of the inner workings of the original building including bars and unused gallows.

About two weeks after Connor reported his description of the inferno to the Macon Beacon, gallows were erected for him across the street from the jail. During the days leading up to Connor’s hanging, he was allowed to preach to crowds of African-Americans that gathered below his window. On Friday, September 26th, 1907, before a crowd that had gathered to witness “the deep damnation of his taking off,” Connor left this world.

Connor walked, dressed almost entirely in black, resolutely to the scaffold and spoke in a strong voice before the noose placed over his neck and the trap sprung. The paper describes the scene with a sense of wonderment. “There were curious ejaculations as to the expressions of wonder at the nerve he exhibited in the face of horrible death, and there were—from the emotional members of his own race—exclamations of admiration for his courage and his religious faith that braved the terrors of the unknown future.”

According to Alan Brown, inmates of the jail reported that Connor continued to make appearances within the building and that his spirit still abides in the library that once held him. Perhaps this Mississippi Dante is still trying to save the living souls of Noxubee County.

Sources

- Brown, Alan. Stories from the Haunted South. Oxford, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2004.

- Federal Writers’ Project of the Works Progress Administration. Mississippi: A Guide to the Magnolia State. New York: Viking Press, 1938.

- “The Hanging.” Macon Beacon. 28 September 1907.

- Macon, Mississippi. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Accessed 11 August 2010.

- Newsome, Paul & William C. Allen. National Register of Historic Places Nomination form for the Old Noxubee County Jail. 28 September 1978.

- “A Noxubee Dante.” Macon Beacon. 14 September 1907.

- “Noxubee’s New Jail.” Macon Beacon. 11 May 1907.

- Rowland, Dunbar. Mississippi: Comprising Sketches of Counties, Towns, Events, Institutions and Persons Arranged in Cyclopedic Form, Vol. II, L-Z. Atlanta: Southern Historical Publishing Association, 1907.

- Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Accessed 11 August 2010.